Tomás Rivera and the Importance of Bilingual Education

Texas State University is located here in San Marcos, Texas. Because educator and writer Tomás Rivera attended Texas State (back when it was called Southwest University), and because Rivera went on to become the first Hispanic Chancellor at the University of California at Riverside, and was the first recipient of the Quinto Sol litereray award for Y no se lo trago la tierra, there is now an annual Children’s Book Award given in honor of Tomas Rivera. All year long I have been using Tomas Rivera books to teach issues of social justice and pride in Mexican-American culture.

Here in Texas, being Hispanic and being bilingual is not always celebrated. In fact, bilingual children are often viewed as having a huge deficit – they don’t speak English and the number one goal of many Texan schools is to get them speaking English as soon as possible. Speaking Spanish is not valued. My mom loves telling me about her elementary school experience growing up in San Antonio’s Westside barrio, a huge Hispanic area. She was not allowed to speak Spanish in school. Any student caught speaking Spanish would have to stand in a corner. Luckily for me, going to school in the late 60’s and early 70’s, I was allowed to speak Spanish, but the goal was for me to learn English quickly. I have been teaching for 20 years now in bilingual classes. Each year I get some student telling me proudly, telling me in a boastful way “I don’t even speak Spanish anymore! I can’t remember it.” And over the years I have had many parents ask that their child NOT be placed in my room because I work with the “dumb” students, the “slow” children, that is, the bilingual children.

I write this information down so you get a feel of what it is like to work with Spanish-speaking children in this small town of San Marcos. However, even when I taught in Austin, the hip, “progressive” capital of Texas, I ran into the same biases against bilingual children. For that reason, I make it a point to let my students know how proud I am to be bilingual, y que es importante de no perder mi español, el español que aprendí de mis queridos abuelitos. Hablo español porque lo aprendí desde niña oyendo a mis abuelitos, mi madrina, mis tíos y tías, pero no estudié en español y no sé mucho sobre todas las reglas gramáticas. I just know “what sounds right”!

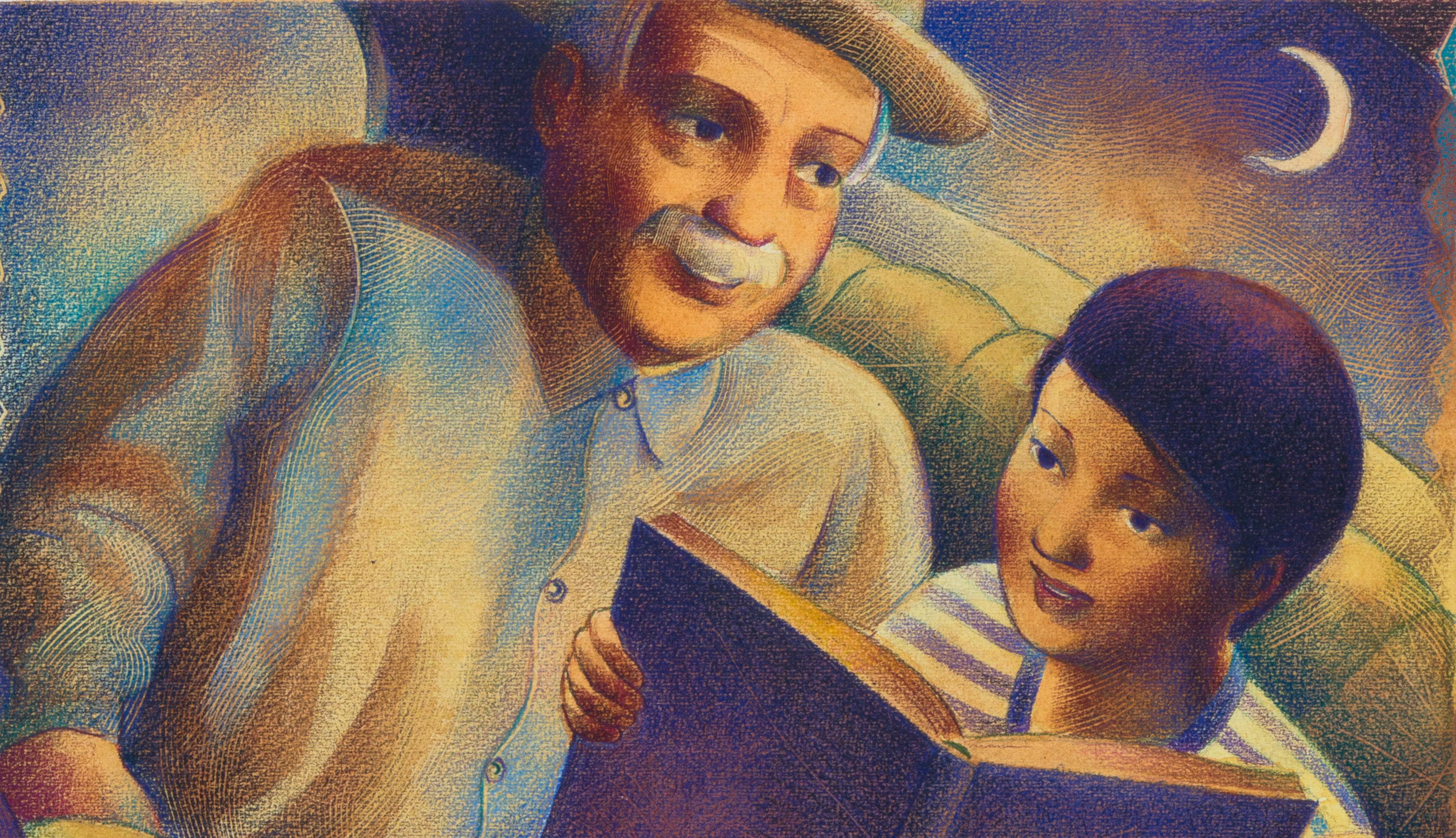

From the beginning of the year we have been reading lots of Tomás Rivera books including Tomás and the Library Lady by Pat Mora. That way my students know who Tomás Rivera was, why he is important, and how he has a connection to our town. I have many lessons based on these books, but I am sharing how I used Carmen Tafolla’s What Can You Do With A Paleta?.

Lesson Plan for Odes that Celebrate Students’ Cultures

This reading/writing lesson takes about 3 days to complete, 30 to 40 minutes per session. What Can You Do with a Paleta? is a picture book that describes the many ways you can enjoy a paleta. I point out to the students how the illustrator, Yuyi Morales, paints the barrio in beautiful, bright colors. The book, though seemingly simple, is to me, celebrating a Hispanic barrio, and celebrating the paletero, the man who pushes his ice cream cart through barrios in the summer. Tafolla’s prose has a great, joyful rhythm to it. She is having fun with words.

After reading the book together and discussing connections to our own barrios, I ask the children to share what other traditions are seen in Hispanic barrios: piñatas, enchiladas, quinceañeras, barbacoa, raspas, tortillas, mariachis, etc. Once we have a good list, I explain what an ode is, a poem written to praise a thing, or a person. I also show the students examples of silly odes as I have lots of children’s poetry books in my classroom (Ode to spaghetti or Ode to pizza, for example). The children pick a topic for their ode and begin their “sloppy copy” (jotting down your first ideas). Once children are happy with what they wrote, they are given lined paper where they can neatly publish their poem. Students then share out their poems with one another, or sometimes we do a gallery walk. Children put the poems on their desks and walk around to read other classmates’ poems. You can see two example odes by my students in the attachment below.

I want to explicitly explain that I see this as a social justice lesson because the writing is meant to celebrate Hispanic culture, or if once in a while I have an African-American child, or an Anglo student, their poems celebrate their traditions. In general, the children I work with come from low-socioeconomic backgrounds and are tagged as “at-risk” from the moment they step into the school system – at risk due to their poverty and their Spanish speaker status. I want my students to feel great about being bilingual. I want them to feel school is there to reflect their stories, their identities, too. School should be joyful, child-centered, and include the stories and histories of people who are NOT usually included in history texts.

In reality, many schools in Texas are about teaching children to pass state-mandated tests. I hope my way of teaching provides my students with a bright spot, and gives them the means to feel proud, feel like problem-solvers, feel like school is really there to help them become the best they can be. Quiero que vengan a mi salon con alegría y amor y paz.

Resource Attachment: Example Odes by Children